I wrote this while listening to Beata Viscera, by Perotin, sung by the Hilliard Ensemble. Click to Listen!

Do we really have to pass things on to the next generation? With what grace does the new come, and the old stay, or indeed go?

After thirteen years away, I have come back today to Yale, the place where my proper pursuit of architecture began. I owe my time here to Alec Purves, who was associate dean of the school when I applied. While I was unreachable, drawing Buddhist temples in the Korean countryside, Alec was calling my mother in Oregon, explaining how Yale would be a transformational experience, and better than Harvard or Princeton, where I had always thought I would go. Something in my mother was moved by Alec’s gentle persistence, and a sense of integrity and conviction in his voice. I myself was convinced, and I soon found myself in New Haven.

Alec was true to his word: Yale was indeed transformational. He guided my design in second year as I imagined an Anglican monastery made of a labyrinthine double spiral. It centred on a chapel made entirely of layers upon layer of laminated glass, wrapped with tall, narrow stone spaces inscribed with scripture by the resident monks. From day to day, I felt an unfolding within my heart. Architecture could hold meaning, and the material or detail of its execution could have as much significance as the general shape and function of its form and spaces. Alec taught me the sensitivity and persistence needed to search for meaning in every move I made as a designer.

This ethos has never left me. Today we sat at Mory’s* for three hours, combing through every detail of the projects my studio has designed and built over the past eight years. The same gentle but relentless questioning, the same thoughtful analysis continued even beyond lunch as we walked the campus touring the many new buildings that have been added since my last time visiting. We must have appeared an odd pair: a white-haired man in his 80’s and a middle-aged Korean stooping down to knock at a bit of aluminium trim here, a bit of stone detailing there, and checking the quality of brick ageing elsewhere. We celebrated some of the winning details, and lamented some of the architecture that was already ageing poorly after a short time.

Grandchild, I hope you will always leave enough time for important appointments. Even with nearly four hours together, the time felt too short, and I had to rush off to meet Trattie Davies, one of my classmates from Yale. For more than forty years, Alec has been teaching the Introduction to Architecture class, and Trattie is teaching with him now that he is getting older. Trattie and I spoke of how much impact Alec has had on decades of students, and how difficult it is to imagine handing over the reins of such a role.

As we shared stories and thoughts, Trattie and I were joined by Tian Hsu, my brilliant young intern from our GenZ programme last year. Tian is a force of nature and so full of energy and passion for design. We took a long walk through the campus and I continued with my knocking on corners, frames, panels, and we again must have looked an odd pair: a middle aged man and a first year student banging away on buildings in the darkening November night. We visited Beineke Rare Books library, enthralled by the brass and stone details, and were blown away by the beauty of Kroon Hall, the school of environment and forestry designed by Hopkins Architects with Atelier Ten, where your grandmother works.

I reflect now on the journey of the day, from James Gamble Rogers and the 19th century collegiate gothic architecture, to Gordon Bunshaft and Paul Rudolph making their modernist mark on Yale, and then Michael and Patty Hopkins, Norman Foster, and Robert A.M. Stern’s studio as well.

As I I banged away on the buildings, it warmed my heart to see Tian also investigating bolts and detail connections in the beautiful timber structure of Kroon Hall. Next year she may have Alec or Trattie teaching her first class of formal introduction to architecture. How incredible that these generations of designers could all come together in a single day - all of us brought together by a love for design and an insatiable curiosity about our buildings, our cities, and how things are made.

I told Alec today of Renzo Piano’s quote: “Buildings are like children. You want then to have a good life.”

I wonder if buildings could speak, whether they would share the same intense feelings that I had today with an eighteen and an eighty-year old.

Would the old buildings look on to the new ones and hope for them a happy and distinguished life? Would there be a day when even James Gamble Roger’s Harkness Tower might have to move aside for another generation of buildings? It fills me with deep melancholy to imagine it. And yet time moves inexorably on.

I feel so lucky to have these people and these buildings in my life. A day like today in New Haven is unmeasurably precious. These days define our lives.

Someday you will also be that young one who stands side by side with your father, with me, and all of the generations that came before. And some day you will be the elder one, watching the youth spring up around you. I hope that all of us can stand tall and celebrate our positive intention for the world.

With love,

Your grandfather. 16 November 2022, New Haven and New York.

Dear Grandchild,

(push the "play button above and listen to Arirang at Seongyojang while reading this letter).

I began writing you these letters to hold myself accountable to you and your generation. How would you judge the choices I have made? Have I lived an honourable life? Am I doing enough to make the world a better place for you to live? I thought that you would help me hold the course and take the right path, even when it was not the easier one.

Eight years have passed, and your father who was a baby is now almost ten years old. I have just returned from a trip to our homeland for the first time since the Covid outbreak.

There is a place in the far eastern mountains of Korea called SeonGyoJang. Tucked in a valley, near the DongHae sea, it is the birthplace of my mentor and friend Yi Ki-Ung. I can see it now in my mind’s eye: a perfectly balanced collection of traditional Korean tiled houses, swaying pine trees, and a pavilion hovering over a pond of giant lotus flowers. There it has stood for more than two hundred and fifty years, the home of a single family that has maintained its buildings and the values that they cherish: year after year, generation after generation.

Mr. Yi founded Paju Book City, and like you, he has been my compass and guide on this journey of architecture. With Mr. Yi turning 82 this year, I felt a strong urge to go with him to his birth home. SeonGyoJang is for him an anchor of meaning and a source of strength, and I wanted to experience that with him first hand, while we still have the time.

It was a long and arduous journey for me: an unbroken forty-eight hours from home to Heathrow, through Frankfurt, Inchon, and then a drive east across the whole of Korea.

More than a house, SeonGyoJang is a collection of courtyards, gardens, pavilions, and traditional tile-roofed Hanok. Everything about Mr. Yi: his grace, his dignity, and his thoughtful sensitivity, are mirrored in the architecture of the place. For an architect like me, buildings like this are sacred, embodying the essential ideals of my heritage and culture.

There was a music festival taking place. Ambling up the hill, we were met with the sounds of a string quartet playing in a stone amphitheatre built into the earth, below soaring Korean pines. Arirang, the music I am listening to now: a traditional song about parting, love, and bitterness.

In a bright yellow dress and a wide-brimmed hat, the great-niece of Mr. Yi greeted me in that place. We were the two young ones among the many older family members as we shared food, looked at art, and walked the nearby beach.

In Korea, we say, “eo-reo-shin mo-shi-da.” Younger ones carefully accompany our elders where they wish to go. Mo-shi-da means to accompany with reverence, respect, and patience.

I felt a kinship with this great-niece as we accompanied the elders through conversation and time spent together. In their presence we took care with every word and every movement. There was a reverence going beyond simple politeness or manners. Shoulders slightly bowed, objects held with two hands, and awkward modesty when receiving praise. All these things we shared and communicated, though between us few words were spoken.

I realise as I write that my approach to design and architecture is also like this. I hope to show reverence to our environment, to have dignity in what I design, and to show humility in my responsibility to care for our world and the buildings in which we live.

In SeonGyoJang, one moves from walled courtyard to walled courtyard. In Korean Hanok, gates have a beam at head level, and another beam at the ground level. To walk through these gates one has to bow one's head to pass under the upper beam and take care while stepping over the lower one. The very shape of our architecture encourages us to physically show humility and respectfulness as we use it. How beautiful!

Mr. Yi’s great-niece carries with great dignity the responsibility upholding her family’s tradition and reputation. I also feel that responsibility: the culture and the heritage of our homeland is something to be treasured and cared for. In Korean, I would say “na-ra reul mo-shi da.” I do that, she does that, and those musicians playing Arirang on that sunny afternoon in the eastern mountains of Korea do that as well.

As the words of Arirang say: “Na reul beori-go ga-shineun nim eun ship-ri-do mot ga-seo bal-byeong nan-da.” Who casts me aside and leaves me behind, won’t make it 10 "li" without their feet failing them. *

My grandchild, please remember our culture, please cherish it as I do, and remember that only by living with it from day to day can we keep it alive. Na-ra reul moshi-ja.

With love,

Your grandfather, 25 September 2022

* 3 li is about 1 kilometer. bal-byeong nan-da literally means, foot illness strikes them - this is a very difficult phrase to translate into English - it is a beautifully peculiar Korean phrase.

Dear Grandchild,

I wrote this while listening to Fake Plastic Trees, by Radiohead.

How valuable are old things? Old people? Old buildings? Old friends and old traditions?

Today I had a long call with my friend Patrick Giannini from Yale Architecture School, nearly twenty years ago now. Patrick was the one who inspired me most at Yale—always creating something unusual and unforgettable. One day it was a set of three faceted houses that emerged one from another like a living outcrop of geometric rock. Another day it was a copper-plate print where the metal had been left to rust in the rain, then pressed into paper to make unbelievable textures of green and blue. And day after day, all kinds of other unexpected things. Patrick has these huge, crystalline blue eyes, and I imagined him as some future being who saw the world with twice as many rays of light as the rest of us.

Today he asked me about making architecture in London, and I told him about my presentation to the city two days ago for the big sculptural pavilion I am working on right now. It’s still confidential, so I can’t name the project, but it definitely won’t be when you read this—remember, the one where Winston Churchill and Lawrence of Arabia used to work? Close to Buckingham Palace? I’m sure I’ve taken you there for a cup of tea or a really tasty cake by now.

I told Patrick that one of the best things about my job is how I get to make really futuristic things in really old places. There is something powerful that stirs in me when I touch a stone today knowing the heroes of the past touched that same stone in their own time. (They say that young Julius Caesar arrived at the Rock of Gibraltar and wept, knowing that Alexander the Great had been there before him).

To work in buildings of such historical importance, I have to work with people who are absolute experts in old buildings. You know that really cool pattern I showed you in the stones of the courtyard? For the presentation the other day, I had to explain that we were going to take those fifty-thousand little cubes of hundred-year-old stone and completely rearrange them to make our own new pattern. Hannah Parham from Donald Insall Associates was there to help me understand how to safeguard the history of the building even as we made our new mark on it.

Hannah is always inspiring me with her uncompromising search for significance. She digs deep into books, grainy photos, and faded newsprint to find the true history of things, giving voice to the forgotten stories of those stones. Hannah has these penetrating brown eyes framed by horn-rimmed spectacles, and I imagine an ancient, righteous power hidden just below the surface of her youthful features. I can picture her as some temple guardian of our precious past.

You know, the future is infinite: it’s full of time, of possibilities, of second and third and fourth chances. But the past—those really important old things that hold the echoes of history and heroes? It’s limited, it’s scarce. And each time we lose some important old thing, we have lost something irreplaceable—because you can’t make something new that has a hundred years of accumulated history.

So these old buildings really do need guarding. They need guardians.

And thinking about it more, maybe it’s the same with old friends as it is with old buildings. Maybe a friend like Patrick is a precious and rare thing as well. I could always make a new friend, but if I lost Patrick I would lose those twenty years of shared moments. The shared stories of youth—learning how to see the world as an architect and artist, for the first time, through Patrick’s crystal-blue eyes. Maybe that friendship is worth guarding, because I will never have an opportunity to make that history again.

I’ve been writing these letters to you for a while now. By the time you read this, I will be an old man. Your grandfather. Another irreplaceable piece of the past. You only have four of us grandparents and when you lose us that’s it. Be a good guardian like Hannah. Do look ahead to amazing futures, but remember that no matter how bright and shiny your new things might be, you will never get back those important pieces of your past, once we’re gone.

With great love,

Your grandfather. London, 24 May 2020.

p.s. the world has been locked down for about two months because of a virus called COVID-19, that selectively kills the old. The crisis will certainly be forgotten by the time you are reading this, but I should tell you, as right now it totally defines our lives and it would be strange not to mention it.

Why strive for beauty? Why seek transcendence? Why hope to create things that will outlast me, to be cared for and loved by others long after I am gone?

I didn’t come looking for answers to those questions today, in a meeting with a dozen engineers and neuroscientists. My mission at Arup this afternoon was to imagine how to measurably improve the wellbeing and enjoyment of two thousand employees in their new office space. But by the time we all went home that night, it was those deeper, more fundamental questions that played again and again in my mind.

Tristram Carfrae was the one to bring us all together. Like me, he enjoys getting to the root of things. And so he invited a couple named Alicia Fortinberry and Bob Murray to speak to us about their findings on the genetic basis for human needs and wellness.

Searching for the roots of who we are as humans, Alicia and Bob looked to the distant past. Before agriculture, before civilisation, and certainly before working in office buildings forty hours a week, our ancestors lived for thousands of generations as hunter gatherers in delicate balance with nature. Our physiology and our psychology are much more imprinted by that ancient life in forest and savannah than by the urban lifestyle that began with the agricultural revolution twelve thousand years ago.

What bearing does that have on architecture and design? Alicia and Bob explained to us that the survival of early humans was based on our ability to form strong social bonds. We have short teeth, no claws, and weak muscles compared to other apex predators. For our hunting and gathering forebears, the group was the key to survival, and expulsion from the band or tribe was equivalent to a death sentence. And so, they explain, our greatest fear is the possibility of rejection and social isolation. Studies have shown that the underlying motivation for most of our behaviour, even in the context of a contemporary office job, is this basic biological need for belonging to a tribe or group. We constantly strive for close relationships, seek social acceptance, and hold on to security while fearing change.

But we no longer roam in bands of thirty, hunting and foraging in a simple but timeless routine. Our lives are deeply complex, interwoven with vast numbers of other people and subject to extraordinary change. Technology allows us to extend our reach, stretch our consciousness, and expand our influence beyond anything imaginable before. And yet according to Alicia and Bob, this extending, stretching, and expanding can cause us psychological strain.

In my time, a typical office worker flies around the world in airplanes, holds teleconferences with people in different cities, and receives hundreds of electronic messages each day. Through technology, we are also learning how to optimise workers’ time and utilisation of space. “Agile” work practices allow us to pack in more workers into a smaller space by shifting them around day to day and eliminating unused desks. Adaptive resource management is finding ways to reduce down-time of workers by shifting them from task to task and team to team without gaps of “unproductive” time. All of this increases productivity and drives progress.

And yet the pace of this constant change becomes overwhelming to many of us. Alicia and I talked at length about this during dinner. Our bodies are literally programmed to seek security in groups through close relationships and stable bonds. And yet our world is increasingly exposing us to a maelstrom of change. When all that is solid melts into air, can we still feel a sense of belonging and find a stable reference point that grounds us within a group?

Alicia and I imagined that the more intense the change we face on one hand, the greater the need for an anchoring identity on the other. The more we ask our workers to extend and stretch and expand, the more we need to provide them with fixed reference points that remind them they are still safe, secure, and part of a group they know. This is a critical task of all of us as designers.

You remember that when I established my design studio our goal was to measurably improve wellbeing through innovative and beautiful designs. It was always easy to understand how innovation and technology like sensors, measurements, and data analytics would be core to our mission. But beauty? After this long day at Arup I feel a renewed confidence that beauty is also essential to our mission. Now I understand that there could be something in our psychology, daresay even in our genetic blueprint as humans, that needs incredible stories, anchoring rituals, and objects of exquisite beauty. Perhaps we need to have around us something worth preserving, something that transcends the day to day, and helps to anchor us with a lasting sense of identity—not only as individuals, but also as groups.

Tristram seems to have an instinct for that fact. And perhaps Ove Arup knew this as well. The group he created has lasted more than thirty years after his death, and I imagine it will still be famous when you are old enough to read this. No wonder he was my role model for setting up my own studio (decades ago, by the time you read this).

All best wishes, your grandfather. 2 February 2018. While listening to Steep Hills of Vicodin Tears, by A Winged Victory for the Sullen.

Dear Grandchild,

Today was one thousand and one days since setting up this studio and beginning to write you these letters.

I wonder how long people will live when you read this letter. In my day, the average life expectancy of someone born in this country, is 81.6 years, or almost 30,000 days. To know the measure of a thousand days, I picture my lifetime compressed down to a single month. This thousand-day journey would have taken a day from that month-long life.

I imagine myself setting out on a long walk at the first hint of sun rising on the horizon. Where would I go, and what could I see? Night falls. I continue through twilight, midnight, and the dark hours before dawn. As rose-coloured light fills the east, I know the sun is coming and only twenty-nine days remain of a brief span on this earth. Have I accomplished what I set out to do on this precious day? Have I made the right choices? Should I have taken a different path?

A thousand days is a long time to spend on any endeavour, and this one has been no different. To spend a thousand days is to continue, day on day, week on week, through all the highs and lows, through days of feeling strong and days of feeling weak. To persevere for this duration requires a certain structure and a certain discipline. Years of working in office buildings have developed in me the rigor of just showing up—just being there every morning, five days a week, fifty-two weeks a year. The “place” in a workplace is so important for any journey like this one.

Yesterday I visited the Shard to see the site for our latest project. In our day the Shard is the tallest building in all of Europe. It stands as a tall crystal pyramid overlooking the Thames. One can see it from all corners of London—even from our house on distant Barnsbury Hill. We are designing experimental work areas on the twelfth floor for a company called Mitie. These “biophilic” spaces will immerse the workers in natural materials, rich textures, and dynamic light.

As we measure the effects of those spaces on the employees there, we hope to learn more about what factors will help them feel stronger, more focused, and more motivated at their daily jobs. Day in, day out, the workers will spend time in these spaces that your grandfather has created for them. Will these spaces help those people take their own thousand day journeys? Will they add meaning and richness to the days spent working? I hope so.

All best wishes, your grandfather. 13 September 2017.

p.s. from today I began writing down the music I was listening to while writing you these letters. Today was: Birth – Piano and String Quintet, by Dario Faini, Dardust.

Dear Grandchild,

Last Thursday I had lunch on a hill overlooking Imjin River and North Korea. Lee Hwangu Sangmunim and I had made an appointment with Ms. Kim, a graphic designer who runs a company called Design Vita. She saw my designs the Rainbow Building and felt that our approach to design is sympathetic to hers. This was our second meeting, and knowing that I enjoy health-conscious food, she took us to the Jeonmang-dae Porridge and Chicken restaurant near Heyri. At this restaurant they raise their own chickens and grow their own vegetables. It seems to be the last place before the demilitarised zone between South and North Korea.

I hope that by the time you read this letter the demilitarised zone no longer exists, and that people can freely travel across the whole Korean peninsula. What had been a single country since the seventh century was partitioned into two countries seventy years ago. As one of last vestiges of authoritarian communist rule, the North lives now in conditions of great poverty. Someday if the border does open, there will be a great need for sensitive and thoughtful development, and it is my dream to play a role in that work.

From our lunch table we were able to see across the river to a small village on the North Korean side. As we spent the meal conversing about studio culture and the book, “Sapiens,” that we had all recently read, I found myself thinking ahead to the future.

Right now our little studio is small, and taking its little baby steps. I do hope that we will evolve to be a beautiful and flourishing office that is capable of taking on substantial work like the planning of North Korean cities. But for now it has been the right decision to take care and grow slowly. Growth is important, but it needs strong foundations.

Culture is something delicate in its infancy, but incredibly resilient once it has taken root. Each month Ms. Kim buys a book for everyone in her studio, and they read it together and discuss it. Sharing ideas and talking about the work we do in the context of society as a whole is one way of building a common culture. When I told Beth and Weronika about that idea this week, they both enthusiastically supported the idea. Perhaps we will have a go.

Those in North Korea have lived in a different kind of culture to ours for seventy years. But I take faith in the fact that they shared with us a common culture for more than a thousand years before that. Someday when it becomes possible for us to get to know one another again, we may find there is more that brings us together than hold us apart. I hope that when that time comes, I will be ready.

All best wishes, your grandfather. 25 November 2016.

Dear Grandchild,

“Success has many fathers, while failure is an orphan.”

Hello again after quite some time. In our days something called Youtube is super popular: people post music, videos, films, and pretty much any moving thing you can imagine onto it. They often criticise it as an enormous outlet for time-wasting for the entire global population. Videos of cats doing strange things get millions of views. Usually I watch it for a laugh, or to learn a new wiring technique for electronics, or how to cook something new.

But tonight I spent twenty minutes watching a guy named Pharrell Williams interview a guy named Usher. By your time they will probably be hobbling around on canes. But right now they are exceptionally talented and successful singers, dancers, producers, and artists. A couple of moments stood out to me and I wanted to share them with you.

After talking at length about authenticity, inspiration, and love, Pharrell just went straight out and asked Usher what he thought was the most essential element of his success. Was it the dance moves, the magnetism, the spectacle? Usher said it was his voice. At the end of the day, a dance move might be amazing but someone can copy it. The same with the spectacle. But the voice, the voice is unique to him and him alone. It is not only the product of years of physical training and practice, but also the accumulation of a million experiences, inspirations, and judgments taken, expressed in just his own way.

In this age, my peers and I are grappling with the ascendance of technology. Because so much of what we do as architects is digital, so much of it can be lifted, copied, mixed, and remixed in the blink of an eye. It is easy to complain that something nice I made was so quickly picked up and copied by someone else, and now it seems they’re getting the credit. I think Usher’s lesson is a good one to we architects as well. If we want to create something unique and magnetic, with staying power even to your generation, we have to make it with our voice. We have to move beyond technique and through to the soul.

The other quote, the one that opens this letter acknowledges the many streams that flow into us to make us who we are. We are on a constant search for springs of inspiration and rivers of support. We can never stand still, never cut ourselves off, and never stop feeding that soul and that voice, lest our flowing water dries up and comes to an end.

All best wishes, your grandfather. 17 October 2016.

Dear Grandchild,

I am just returning from a short trip to Korea. I was there to present my proposal for the Genius Republic guest houses in a secluded mountain valley four hours from Seoul. My trip has been a successful one–the proposals that I made to the county governor were accepted as a basis for the project, and now we have only to find a way to transform these ideas into a reality.

This project has a special significance in relation to these letters, because it is a project that will literally grow up with your father. My proposal is an unconventional one: to completely integrate a village of guest houses into an enormous working apple orchard. The lines of trees will create serpentine paths through the landscape, and when they open into glades small houses will be revealed within. Visitors will be able to pick their own apples and also learn organic gardening and farming techniques.

We will plant small nursery trees next year–if we use the two year old trees that we have been planning, they will be the same age as your father, and would be thick-trunked, beautiful old apple trees by the time you are born. The variety is likely to be the Alps Otome mini apple, that can be grown in Cheongsong without chemical pesticides.

Apple trees have beautiful white flowers in the spring, thick green leaves in the summer, red fruits in the fall, and bare brown branches in the winter. I love the idea of a whole village changing colour and texture from season to season.

My hope is that by promoting a more integrated architecture that interlocks organically with cultivation, that all of us will develop a keener awareness of the rhythms of life. It is all well and good to put architecture in a beautiful natural setting, but if can also encourage ourselves to re-engage with the very fundamentals of our environment and our health, we will have achieved a little more. I believe that creating a hybrid agriculture and architecture development can take us in this direction.

Working in Korea is a challenge, and I feel that more sharply every time I have a meeting in London that requires nothing more than a short trip on a bicycle. But for a project like this, with aspirations of this kind, I do think it is worth it. I hope that someday I can take you there myself, and we can pick apples as we walk through the architecture that I have made.

All best wishes, your grandfather. 2 August 2015.

Dear Grandchild,

Today I was at the Greenwich Maritime Museum, for a competitive interview. I am collaborating with our friend Tanvir Hasan and her office to bid for the job of restoring and designing a new wing of the museum. This collaboration with Donald Insall Associates is a very optimistic one for me. Their office focuses on historic preservation, and does much work with castles and old houses. Many of their projects are hundreds of years old.

Why is this interesting for a young architect like me who is completely focused on innovation through design? Practically speaking, there is a good synergy here. Many restoration projects also involve upgrading amenities to modern needs and regulations. When adding new stairs or pavilions or kiosks to a historic building, sometimes it is better to do something light and contemporary, to completely contrast with the old fabric. And so these kinds of structures can be designed by me.

At a deeper philosophical level, there is something more to be gained by this collaboration. My goal is not to make buildings that look futuristic, but to design for our future generations. I want to design buildings not just for all of us now, but for you and all of your friends and colleagues, and even for your children and grandchildren. To achieve this, first of all my design has to have staying power. It must be robust enough that people want to preserve it rather than knocking it down and building something new again. And secondly it must be detailed and constructed in a way that can really last.

Tanvir and her colleagues at Donald Insall Associates have a deep understanding of both of these qualities. The buildings they restore were the most innovative and excellent buildings of the eras when they were built. Through the process of careful conservation and restoration, Tanvir and her colleagues have absorbed an incredible amount of knowledge about materials, technology, and time in architecture.

Although I use new materials and new techniques, I also want to know how I can make buildings that can last for generations.

All best wishes to you. Your grandfather. 6 April 2015

Dear Grandchild,

Today I submitted my very first competition design entry. I did competitions for many years while at Zaha Hadid’s office, but as this is the first one after establishing my studio, I felt it had a special significance.

The project is a pavilion and kiosk to be part of the first Chicago Architecture Biennial this fall. The call for proposals asked for designs that were innovative, achievable, and sustainable. My proposal was to make a pavilion structure that could visualise the air quality of each of the 77 individual districts in Chicago. The pavilion becomes a landmark and nerve centre of information that unites data visualisation with beautiful sculptural forms. With more than four hundred competitors, it is very difficult to judge my chances of winning, but at the very least, the design proposal is one step forward on my agenda of making visible the invisible things in our life that affect our well-being.

Air quality is one of the emblematic topics of my design agenda. It represents a specific challenge because although it has an enormous effect on our collective health, the air itself is largely invisible, the costs are long-term rather than short-term, and the lines of responsibility are highly complex. As an example from our times, huge amounts of pollution in China are being blown across the Seohae sea to Korea. Unlike immigrants or militaries, we cannot turn away the dangerous pollutants at the border.

As architects and stewards of our environment, how can we play a meaningful role in this absolutely crucial issue? So much of the work needs to be handled through policy and regulation, and falls outside of the realm of design.

My hope is that projects like my Chicago Kiosk design proposal can help increase awareness of the problem, not just as a one-time event but as a part of everyday life. Imagine if it would not just be one pavilion, but all of the architecture and environment around us giving us constant visual cues of the state of the air around us, and also helped us to better understand the sources of the problems. We would be halfway there in terms of swaying public opinion.

Competition is challenging, but it gives us the opportunity to refine our thoughts and explore new territory. I hope that by the time you are reading this letters, we will be a few steps further along this path!

All best wishes to you. Your quite tired grandfather. 23 March 2015

Dear Grandchild,

I am back in London after a dizzying site trip to Korea. This has been a week of mustering energy and regrouping for the ongoing campaign. Also of note is that this week I registered my practice at Companies House as a Limited Company.

When I first read Ove Arup’s Key Speech, describing his philosophy of design and philosophy of life to his colleagues, I remember being struck by the amount of time he dedicated to management, money, and other mundane practicalities of company administration. Over the years, I have come to appreciate the importance of that thinking. Taking our ideals and turning them into reality requires coordination and organisation as much as it requires philosophy and beliefs. And as I issue myself the first one hundred shares of my company, I already think about management structures that might allow me to attract the most talented and ambitious people, and build with them a company and a home worth growing and protecting for this generation and the next.

Last weekend our guests for lunch were Cynthia Oakes and Hattie Hartman and Josué Tanaka. All three of them are friends through our Princeton connection, and with them we had a delightful meal and long walk around the flower market and the farm. Hattie and Josué are real kindred spirits to us, having devoted much of their professional energy to sustainability and the built environment, much as we hope to do. Cynthia is a woman of enormous energy and a knack for discovering kindred spirits who don’t know one another yet. She took great pleasure in introducing us to Hattie and Josue some time ago at her home.

The conversation ranged from updates about my projects in Korea, to humorous anecdotes about eccentric people Josué has met during his years at the European Bank, to thorny questions of how much concern we in London should have for those in the more distant corners of the United Kingdom. Although decades have passed since any of us sat in the dining halls at Princeton, the meal was very much like the ones I remember from my university days.

Those of us who attended Princeton are bound together by the common threads of intellectual curiosity, drive for excellence, and desire to shape the world in which we live. Two hundred and sixty-nine years of graduates have woven a rich tapestry of lives and work. Arup founded his company sixty-nine years ago, and it is still going strong. I do believe that to have a rich and lasting impact, we must not rest just on our idealistic principles, but find those very practical ways in which to administer them and grow them over time.

With my warmest wishes to you. Your grandfather. 1 February 2015.

Dear Grandchild,

It is Sunday evening, and this brings an end to an intense and social weekend. I would like to tell you about three of the guests who came to our home yesterday and today.

Yesterday the photographer Yuki Sugiura came for lunch with her partner Simon, who is a product designer. I met Yuki on the plane returning from my Building Green lecture in Copenhagen last October. We had noticed one another at the dining room at Bror restaurant the previous evening, and as we happened to be on the same flight back to London, struck up conversation at the immigration queue when we arrived at Heathrow.

Bror restaurant was established by chefs who had trained at the celebrated Noma restaurant in Copenhagen, and so I felt some kinship with those who had also struck out from under the shelter of a world-famous establishment. I wish I had more space here to tell you about Bror, but I am afraid you will just have to dig it out of my black sketchbook from that time.

Yuki is a well-established food photographer, and the work she does is in my estimation closer to art than to documentation. Knowing her passion for food, your grandmother cooked an overwhelming array of traditional Korean foods. Of particular note was the GuJeolPan royal dish that she served in your great-great-grandmother’s sterling silver octagonal box. Your great-great-grandmother learned to prepare that dish from the head of the last royal kitchen of Korea, and she taught your grandmother when we were married. I hope that you will learn from your grandmother, and that the tradition, and that beautiful silver box, will live on in an unbroken line with you.

This evening, the fashion designer Yoojin Kim came to visit us for tea and examine my wardrobe. Yoojin approached me because of her interest in bringing exceptional fashion design to the wardrobes of the bicycle-to-work generation of London men. She saw my interest in the topic on Facebook and asked to see us. She has fantastic ideas about reversible suit jackets and collar lapels that flip up to reveal reflective fabric, and design of details for mobility. Although she is only in her early twenties, she shows incredible focus, and your grandmother thinks that she will be a well-known and successful designer someday. Depending on circumstance, we may ask her to design my work uniform.

After a weekend like this I feel more and more certain that our future as designers is to bring together these diverse fields, and through them become curators of beautiful and healthy lives.

Wishing you all the best, your grandfather. 11 January, 2015.

Dear Grandchild,

It is late on a Sunday night, and I have been working quite a bit today and yesterday on drawings and images for the Communique Headquarters in Seoul. This past Wednesday was my first day working completely for myself, and because I somehow caught a cold on the trip to Saudi, I had to make up a bit of the time working this weekend. Tomorrow evening I will speak with the client and present my new ideas for the ground floor outdoor space.

Besides doing my last site walk on the KAPSARC project and having my last day at Zaha Hadid’s office, and my first day with my own office, the highlight of my week was meeting Jane Wernick on Thursday. Miya Ushida introduced me to Jane, telling me that she might be able to give me some structural advice for the Communique project and potentially push the design forward. It would not do justice to Jane to call her an engineer. I found that she was a thinker and designer who has a deep curiosity for all of the ways that the built environment can influence our lives.

I am reading Jane’s book on Building Happiness right now. She was the editor, and many of the contributors are from her group called Building Futures at the Royal Institute of British Architects. The group is dedicated to promoting discussion about the future of the built environment in twenty to fifty years’ time. So on a larger scale, these people are aiming to achieve something similar to what I do when I write you these letters. And although I talk about well-being, and Jane talks about happiness, it may be that we are aiming for similar things.

I spent an hour with Jane on Thursday, four hours with Rob Stuart-Smith and Shajay Bhooshan at the AA’s Design Research Lab reviews on Friday morning, and about twenty-six hours working on the Communique Headquarters from Wednesday until today. I do believe that dedicated time producing work and real buildings provides an important anchor to our lives and our work. At the same time, a portion of that time really must be spent exchanging ideas and building coalitions with people who share our values.

Jane encouraged me to collaborate with statisticians and academics who can help me really quantify and demonstrate the claims that I hope to make. That will mean that I have to reach out even more and create new collaborations. All of that takes time away from simply sitting down and producing drawings and models for architecture. Finding the right balance between these two conflicting demands will be one of the great tasks of the coming year.

All best wishes, your grandfather. 21 December, 2014.

Dear Grandchild,

It is Sunday night and I am awake in Saudi Arabia. This is a significant moment for me. Last week I said farewell to all of my colleagues at Zaha Hadid’s office, and today I have arrived in Riyadh for my very last act on behalf of the office. I am here for one last site visit to the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center.

This is the project that started me on my course. It was a turning point for me because it was the first project where I had the opportunity to make sustainability the explicit agenda of my design approach. The LEED Platinum certification we used for the design was my first exposure to benchmarking, and helped me to better understand the importance of measurement in communicating design intentions.

It is very difficult for me to predict what this part of the world will look like in forty years, or whenever it is that you are old enough to read these letters. In today’s world, Saudi Arabia is one of the stable anchors in a region that is torn with strife. Great wars are bringing enormous human suffering to Iraq, to Syria, and to Afghanistan. The stated reasons for the conflicts are religious ones, but there are of course deep political and economic agendas at play as well. The great wealth that comes with the petroleum reserves here in the desert heightens the intensity of it all.

As I leave behind this white, crystalline edifice in the dusty outskirts of Riyadh, I hope that I can someday bring you back here to see the building together. I imagine that its sixty thousand concrete panels will be rough and weathered by years of unyielding sun and bracing sandstorms. I hope that the prevailing winds still come from the north in the spring and the fall, and that we can stand together in one of the research centre courtyards and feel that gently cooling breeze on our faces.

Although the social ambitions of modernists like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright are to me a great inspiration, I would not yet subscribe to their beliefs that architecture is the principle agent for curing the world of its ills. It is Louis Kahn who holds my deepest respect, and I think he might have said that architecture can open our eyes to the world and heal our souls. I still hope to play my part in making the world that welcomes you more beautiful, more just, and less violent. But perhaps this is something that I can quietly do from building to building, and from person to person, rather than imagining broad sweeping gestures of politics and economics from the top.

Thinking fondly of you from Riyadh, your grandfather. 14 December, 2014.

Dear Grandchild,

This has been a very social week, with dinners and lunches with many people in London.

On Tuesday evening your grandmother and I had dinner with Cynthia Oakes, who had wanted us to meet her cousin Hattie, who is a journalist with Architect’s Journal magazine. Hattie has been a great champion of the sustainability agenda from the early days, and it turns out that a profile on Patrick Bellew and Jonathan Smales’s project for the Earth Centre was one of her very first commissions as a journalist. Hattie was so positive and encouraging about the dream of bringing together my passion for innovation and beauty in design with an ambition to measurably improve human well-being through architecture. We will see her again at the end of January, when she and her husband come for a long Sunday lunch at our house.

On Friday, Tanvir invited me to visit her at Insall Architects, where she directs restoration and conservation projects throughout the United Kingdom. Over lunch at the Villandry Café, we talked about the possibility of collaborating together on projects next year. She tells me that while her clients used to ask her office to do the conservation work and give advice for adaptive reuse and extensions, that increasingly clients are simply asking them to take on everything.

Her idea of partnering with young studios like mine is a beautiful idea. It brings together fresh thinking about design and technology with deep experience and understanding of historical architecture and details. This would be an enormous opportunity to learn, and also to have more conversations about the embedded wisdom that we find in vernacular design and details, and how that thinking can enrich contemporary design practice.

Vernacular and historical styles of architecture have an incredible sophistication of technical accomplishment, mainly due to the fact that they evolved through trial and error over hundreds of years. As we design in a contemporary setting, our technical details and material strategies are much more diverse and divergent. Many of the technologies that we use have not been tested for a generation, let alone a century. I believe that we can use computer programming and genetic algorithms to reproduce the deep evolution of style and solutions that historical architecture has traditionally achieved. Learning from Tanvir and her colleagues should help me along in that agenda.

With all warmest wishes, your grandfather. 7 December, 2014.

Dear Grandchild,

Today is my thirty-eighth birthday. Try to imagine that even at this age, I feel incredibly young and green, just learning the basics of architecture. If you can find an old archived copy of Perspecta 37, the journal I edited when I was at Yale, you will see an article by Mark Wigley entitled “How Old is Young,” and perhaps get a sense for how long it takes architects to feel a sense of confidence and mastery of our craft.

I hope that by the time you are reading these letters, I have been able to fulfil my dream of making architecture and environmental education a part of basic education. I believe that everyone should know the fundamentals of how our environment affects our lives, and the role that design and architecture have to play in that story. One reason that we architects take so long to establish ourselves is that we start so late. Most of us only begin studying the craft in university. Today I had lunch with your grandmother and your great-grandparents in Heston Blumenthal’s restaurant at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel. Imagine the fact that I had cooking classes even when I was twelve years old, but only studied architectural history for the first time when I was nearly eighteen. I hope that this has changed by the time you grow up.

I spent the week in Cambodia meeting with Youk and his team about the Sleuk Rith Institute. The highlight of my trip was a short conversation I had with a young lady at the Royal University of Fine Arts called Boramy Sina. By the time you read this letter she must be more than fifty years old, and a successful Cambodian architect.

Brian and I had just given lectures to the Cambodian architecture students, and Boramy came to ask me why it is that her designs are beautiful when they are in her head, but when she tries to express them in the computer they seem awkward. I told her that the hand and the eye must be constantly trained through practice. Design is expression—a performance—and just as musical performers must practice, so we must draw and sketch constantly, whether with pens or with the computer. I told her about my years of sketching, and the incredible Rome course taught by my mentor Alec Purves at Yale.

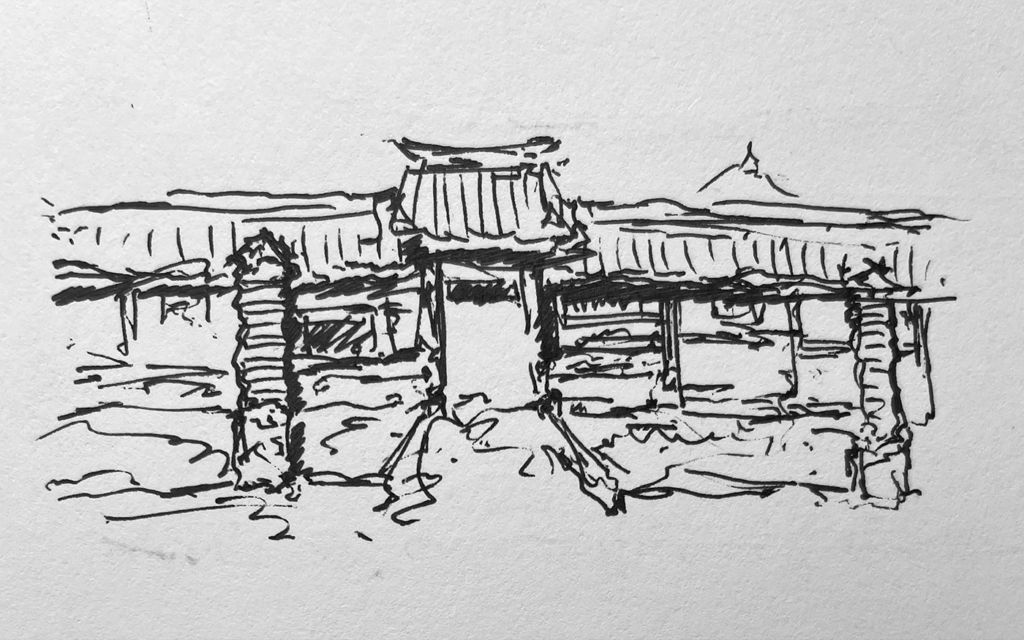

Before I left Cambodia, I visited Chi Soo Temple in Phnom Penh, and drew the plan of the complex from observation. I gave that drawing to Boramy as a gift to inspire her to practice more. Someday I hope that I can create a program like Yale in Rome in Cambodia for Boramy and her fellow students.

With fondest wishes to you on my birthday. Your grandfather. 23 November, 2014.

Dear Grandchild,

This was the week of my annual tradition of having a birthday dinner with many of my architect friends at the HankangPocha Korean restaurant in Soho. Friday was the tenth year of these dinners, although there was one year that I cancelled because of illness. In the first year the location was in the basement on Hanway street, but since then we have had a corner table on the first floor. We have a great deal of Korean bar food, drinks, and I always hand out presents to everyone.

Some of the architects who come every year might be well-known by the time you read this letter. There are Ludovico Lombardi, and Hannes Schafelner, and Daniel Fiser, who have all been coming for a very long time. LisamarieAmbia and Marian Ripoll have missed the last few dinners for different reasons, and Jakub Klaska and Evgeniya Yatsyuk are new to the table, having come just since last year. Rob Stuart-Smith and Marco Vanucci are already fairly well known even now. Sara Akbari, Fernanda Mugnaini, and Stella Dourtme work with us at Zaha Hadid’s office, and Silvia and Cate are the two non-architects in the group.

This year was special not only because it was a tenth anniversary, but also because it was the occasion when I told the group that I was planning to leave Zaha Hadid’s office and start my own studio in London. I wrote individual letters to each of the guests, and gave them out partway through dinner. Everyone was enormously supportive and very optimistic for me. It was a wonderful night.

Reflecting on the gathering, I intuit the importance of creating traditions. We go to that place year after year, and although some people come and others go, there is a feeling that this is something that we always do in November. It frustrates me that we are subject to the fate of the restaurant itself, and that we would lose our locale if it would go out of business. That was one of the reasons I proposed to your grandmother in front of an eight-hundred year old redwood tree rather than in an expensive restaurant that might be gone in a year, or a decade.

Perhaps this possibility of marking the world, and anchoring us—encouraging tradition—is one critical role of architecture. I write quite often about the need for architecture to been in tune with cycles of nature and of time, shedding their skins and taking on new ones. But perhaps it is equally important to build for the ages, and make homes for our traditions.

I hope that by the time you read this letter that some of the people I mentioned above have achieved great recognition by doing great things.

All of my love, Your grandfather. 16 November, 2014.

Dear Grandchild,

It is Wednesday evening. Over the last week I have hit some important milestones. On Monday I submitted the first official draft of my letters from the future article for AD magazine. This is Chris Luebkeman’s issue, where my article is a letter from my 2050 self back to today, critiquing my work and giving me advice. That article is to me a compass and an ideal that I should strive to follow, and it was also the genesis of these letters to you. Writing that article made me realise that it was important that even as I did my work from day to day, that it would be important for me to understand the greater goals and the long-term implications of the decisions that I make.

I hope that this projection to the future will give me a stronger sense of mission and more confidence to strive for higher ideals. At least once a week, I must be doing something that makes the world a better place to live, for you and not just for me.

I was in Copenhagen last Wednesday and Thursday to give a public lecture at the Building Green Conference there. My talk was entitled “Sustainability as a Matter of Form,” and I talked about the need for sustainability to be subtle and fully integrated into the work that we do as designers, rather than applied on top as a layer of technology.

This is very important to me because I believe that so much of the architecture that we do should not feel immediately technical or futuristic. In the case of the Cambodia project that I have designed with Zaha Hadid and the Documentation Centre of Cambodia, the main character of the building should be one of healing and reconciliation. It is the play of shadow, light, and material that must come to the foreground, rather than the energy strategy or the water management approach. As I said to you last week, sometimes the rhetoric of sustainability must give way to the song of form. And so we embed the sustainability deep within the fibres of our buildings—always there yet only sometimes speaking loudly.

Copenhagen was an example of that approach. I had heard so much about the great cycling city, and expected the cycling element of the urban fabric to be extremely visible and very much in my face. And I was so surprised at the subtlety of that system, even though on inspection it permeated every corner of every space. How successful it was. I will take you there someday and we can ride the streets together.

Your grandfather. 5 November, 2014. London

Dear Grandchild,

It is Tuesday evening, and this weekend was busy enough that I postponed writing you until today. Over the past week, work has been much more a matter of traditional design. On the Communique Headquarters, I developed the ground floor café plans of the building. The café is a significant element because it ensures that this private office building will have a public engagement with the neighbourhood.

One small victory for the functional brief of the building was the client’s decision to develop the entire area under the building as an outdoor café space. This means using what was formerly three parking spaces as a covered outdoor area, and fully glazing the two main sides of the ground floor. If executed well, the impact of this development on the neighbourhood should be substantial and positive.

At the same time, the dilemma for the architecture is the fact that a fully glazed café façade affords less possibility for sculptural architectural features. I have been grappling with the question of how best to frame the project in design terms each time the brief has changed.

I have also questioned how a façade pattern or re-cladding of a building in stone can have a strong sustainability and well-being story attached to it. There is a question of façade performance, certainly. But beyond that, is the design of a building envelope pattern mainly an aesthetic concern, particularly when the budget is so limited? This has been a difficult question for me to answer.

While it is true that architectural design touches on issues of human organisation, and that there is an opportunity to influence the way we live as human beings, design is at the same time a very aesthetic act. The shaping of matter, of space, of light, and shadow are truly fundamental to our discipline, and perhaps there are times when the rhetoric of sustainability must give way to the song of form.

Your grandfather. 28 October, 2014. London.

Dear Grandchild,

It is Sunday evening, and I have had an absolutely wonderful week. After working hard for a Friday deadline on my first independent project (Communique New Headquarters, Seoul), I have had a quiet weekend with some time to relax and recuperate from the intensity of the last few days.

Today I cooked a beautiful meal for Linda Lloyd-Jones (head of exhibitions at the Victoria and Albert Museum), and David Lloyd-Jones (pioneer of sustainable architectural design in the United Kingdom). The menu included a selection of French cheeses and sausage, quince, and champagne; Italian bresaola beef drenched in olive oil with black peppercorns and fresh mozzarella, garnished with rocket and pomodorino tomatoes; halved baby gem lettuce with pan fried prawns and soft boiled duck egg, drizzled with spicy honey mustard dressing, and dark chocolate ganache with whipped cream and clementine wedges.

Linda and David are in their sixties, and spending more time with them is part of our family effort to cultivate a more diverse group of friends from all generations and all parts of society. In a way, enjoying wonderful food and finding inspiration from the way they live their lives is just as much about broadening my perspective as are these letters to you. Stepping away from the intensity of design to find harmony and joy through conversation and a shared meal reminds me of the importance of mental tranquillity and stability in our lives and work. I found myself wondering whether we designers could work with that same lightness, joy, and freedom as we design, rather than putting ourselves underthe typical enormous pressure to excel? I was not surprised that the hours I spent working after they left were incredibly productive.

The teleconference with Communique on Friday was a small victory noteworthy for this letter. Through the process of working diligently for the client, maintaining an honest and reasonable dialogue, we have naturally increased the scope of the project to include the reconstruction of the whole façade of the building. Our conversation led the client to realise that rather than spending fifty million won to mask the façade with cheap and short-lived materials, it would be better to spend perhaps sixty or seventy million on a durable, high-performance façade that would last for decades.

In other news, I have started my AD magazine 2050: Designing Our Tomorrow article, which will be my 35-years-from-now self critiquing my work today.

All best wishes, your grandfather. 19 October, 2014. London.

Dear Grandchild,

Hello from 2014! If you are wondering why I write these letters to you when your father is only twenty months old, I can tell you that I am writing them for me as much as I am writing them for you.

This is a year of great transition for me. On the tenth anniversary of moving to London and beginning my training as an architect with Zaha Hadid (she was a famous designer in these days-I’m not sure whether she will still be practicing in your time), I am embarking on my greatest adventure so far. This is the beginning of my office, which I hope, by the time you read this letter, will be a beautiful and flourishing company of people. Now, as I write this letter, it is really just me, a lot of ideals, and some very wonderful friends who give me all their best wishes.

For nearly fourteen months I have been preparing for this day by working tirelessly in every spare moment that has not been taken up by my responsibilities to Zaha Hadid’s office. To give discipline to that work, I made a tradition of keeping a daily log. It is the same kind of record that a captain used to keep on a ship—sometimes filled with mundane accounts of the practicalities and planning of work, and sometimes filled with discoveries, or more abstract ideas. In general, though, it is a simple record of my day to day work.

Today on the 13th of October, I have completed negotiations about my departure from my current employment. I have been considering that a daily record of my work is useful, but that if I am to stay focused on my long-term dreams, that I need something more substantial. These letters are the medium that I have chosen.

Each week, I plan to write you a letter, telling you about the work I have done as a designer, an architect, and a member of our community. These letters are to you, because my ultimate goal is that the work I do today will make a positive impact on the world in which you live. These letters are a way of keeping me honest—making sure that no matter how much I find myself drawn to artistry, or commercial success, or theoretical proposals, that in the end I can say that I am on course.

These reports to a grandchild are therefore a guiding compass for a grandfather, a shouldering of responsibility, and an expression of deep optimism and hope.

With all best wishes, your grandfather, DaeWha.

13 October, 2014. London.